Bluegrass Music’s Family Reunion

OWENSBORO, KENTUCKY, sits on a high clay bank of the Ohio River some170 miles north and east of the Mississippi, right before the bottomland begins to turn into the “knobs” outlying the low plateaus that mount like stairs east across Kentucky to the low wall of the Cumberlands, which are themselves but the foothills of the Appalachians.

From here in western Kentucky the mountains are only a colorfully tough neighborhood—or to the early settlers who crossed through them, a bad memory. In Daviess County the Ohio Valley is wide and flat, and fields of corn, tobacco and soybeans stretch off in every direction as far as the eye can see, and then a little farther. The steepest hills around are the spoil banks of the coal mines toward Muhlenberg and Ohio counties to the south.

In the old days, when the world was young and I was growing up in Owensboro, the air was heavy with the sweet smell of sour mash whiskey and the barns bulged with bright yellow burley tobacco; it was tobacco and bourbon country. Farm country.

For this is not the Bluegrass, the racehorse & white-fence Kentucky; nor is it the steep Cumberlands of the dark coal mines and damp hollers. Yet the broad river-bottoms of Owensboro are laying claim to the heritage of both, as this small river city of 50,000 vies to become the world capital of that intricate, bittersweet, plaintive strain of country music called Bluegrass.

THE INTERNATIONAL BLUEGRASS MUSIC ASSOCIATION operates out of a small office in Owensboro’s sleepy downtown abandoned by the suburban shopping centers and malls. The IBMA was set up some seven years ago, inspired by a progressive mayor (then heading the Chamber of Commerce) and a hip record store owner, both of whom loved Bluegrass. Owensboro needed something, and Bluegrass needed a home if it was to turn its loosely-linked network of players and promoters into an Industry. The first meeting drew a trade magazine publisher, a couple of agents and record company executives, and musicians like Ricky Skaggs, Bill Monroe and Doyle Lawson.

THE INTERNATIONAL BLUEGRASS MUSIC ASSOCIATION operates out of a small office in Owensboro’s sleepy downtown abandoned by the suburban shopping centers and malls. The IBMA was set up some seven years ago, inspired by a progressive mayor (then heading the Chamber of Commerce) and a hip record store owner, both of whom loved Bluegrass. Owensboro needed something, and Bluegrass needed a home if it was to turn its loosely-linked network of players and promoters into an Industry. The first meeting drew a trade magazine publisher, a couple of agents and record company executives, and musicians like Ricky Skaggs, Bill Monroe and Doyle Lawson.

A marriage of convenience as well as love, it turned out to have been a shrewd move on both parts. Two hours from Nashville, Owensboro is just big enough to be a City, just Kentucky enough to be Southern, just rural enough to be Country, and just needy enough seek Opportunity; plus it comes with regionally-famous barbecue and 800 motel rooms. Bluegrass brought to the marriage the legacy of an authentic American folk art combined with the glitter of show business.

These days Country music is hot and Bluegrass burns with an even hotter, if smaller, flame. The IBMA is proud to show off the demographics. Bluegrass fans are younger, better educated, and (yes) more urban than Country fans in general. Which is just another way of saying that they have more money to spend.

The IBMA calls its late September World of Bluegrass convention the “family reunion” of the music, and they‘re not far wrong. The IBMA has grown to two thousand members and now represents virtually every band, agent, record company and promoter in the field. From Monday through Sunday ten thousand pros and fans will pour into the city for a week of making deals, making money, and making music. The Fan Fest, which is a benefit for the Bluegrass Trust Fund and the IBMA, will feature a line-up of stars that no promoter could afford to hire on his own.

The Trade Show comes first. Bluegrass is, after all, a business, and business begins at the Executive Inn downtown on the river. The “Big E” as it is called locally (and not always affectionately) is a generic Peachtree clone, of the kind that now litter the South, with six or seven balconied tiers of rooms around an open court festooned with trees that look (on a good day) like fugitives from a fencerow. No matter. The lobby is filled day and night all week with musicians, promoters, agents, record producers, session men, and record company executives, the kind of people to whom drab hotel decor is as comfortably familiar as the back end of a mule was to their predecessors who first started making the music they now market and sell for a living.

On Thursday the press will arrive for the Awards Show. On Friday the fans will arrive for the Fan Fest. Meanwhile, only the pros are here—the 1500 people who live and breathe the music, including the hundred or so who can make or break a recording, band, or a festival. Monday through Thursday the deals are made, acts are showcased, and amateur awards are judged in the big Pizza Hut competition, with contestants from every part of the country. The winner is an all-women band, Sassygrass, from the Northeast, pointing to new directions. Things are changing. Lyn Morris and Alison Kraus are bandleaders and not just “girl singers,” but the past is still with us. Look around the lobby of the Big E and you will see that Bluegrass today is a music of young women, and old (and young) men.

On Thursday the press will arrive for the Awards Show. On Friday the fans will arrive for the Fan Fest. Meanwhile, only the pros are here—the 1500 people who live and breathe the music, including the hundred or so who can make or break a recording, band, or a festival. Monday through Thursday the deals are made, acts are showcased, and amateur awards are judged in the big Pizza Hut competition, with contestants from every part of the country. The winner is an all-women band, Sassygrass, from the Northeast, pointing to new directions. Things are changing. Lyn Morris and Alison Kraus are bandleaders and not just “girl singers,” but the past is still with us. Look around the lobby of the Big E and you will see that Bluegrass today is a music of young women, and old (and young) men.

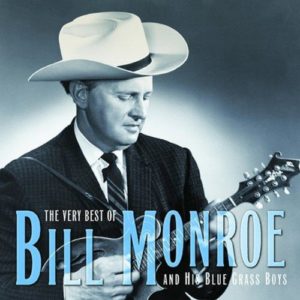

TODAY BLUEGRASS IS FIRMLY ENTRENCHED as the bearer of Country music‘s traditional “soul.” Which is ironic, for while it has traditional roots, it‘s a made-up sound, virtually invented by Bill Monroe and his Bluegrass Boys back in the 1940s. It‘s back porch country string band music “jazzed up” up for homesick Southern workers in Northern cities during World War II. It‘s hillbilly with overdrive. Today the term “bluegrass” is understood to include most of acoustic country music, usually (but not always) leaving out pianos and drums. It‘s the classical mode of Folk—formal, tight, improvisational, with often dazzling speed and precision. A musician‘s music, it is to Country what Bebop is to Jazz, featuring soloists and virtuosity: one at a time, stepping up to a single mike. It was driven underground by the Rock explosion, then resurrected as part of the Folk boom in the 60s.

TODAY BLUEGRASS IS FIRMLY ENTRENCHED as the bearer of Country music‘s traditional “soul.” Which is ironic, for while it has traditional roots, it‘s a made-up sound, virtually invented by Bill Monroe and his Bluegrass Boys back in the 1940s. It‘s back porch country string band music “jazzed up” up for homesick Southern workers in Northern cities during World War II. It‘s hillbilly with overdrive. Today the term “bluegrass” is understood to include most of acoustic country music, usually (but not always) leaving out pianos and drums. It‘s the classical mode of Folk—formal, tight, improvisational, with often dazzling speed and precision. A musician‘s music, it is to Country what Bebop is to Jazz, featuring soloists and virtuosity: one at a time, stepping up to a single mike. It was driven underground by the Rock explosion, then resurrected as part of the Folk boom in the 60s.

When I was in high school, Owensboro was trying to shed its country image, and the only live music to be found was in the little redneck honky-tonks east on Fourth Street or west on Second. A band was a strat, a one-armed drummer, an electric bass and occasionally a fiddle if you couldn‘t afford a pedal steel or a girl vocalist. A mandolin or banjo? Forget it. Bring one of those inside the city limits and you were arrested. Or at least warned.

I was into jazz. Miles, Monk, Mingus, Coltrane. I was lucky enough to have been turned on to Bebop by a genuine NY Beatnik visiting his family in the provinces in the late 50s. He also alerted me to Bluegrass, but I wasn’t paying attention. One night we were driving around, searching for jazz on the AM-only dial, when he came across a wild cascade of notes and said: “This cat is wailing!” he said. “On the banjo!” And so he was. It was probably Earl Scruggs. It should have made me think, but it didn‘t.

OKAY FOLKS, LET’S GET SERIOUS. If you‘re going to have an Industry, you‘ve got to have Awards, and if you‘re going to have Awards you‘ve got to have an Awards Show. The Third Annual International Bluegrass Music Awards Show is the first to be held in Owensboro‘s new Riverpark Performing Arts Center.

Everything here is gray or charcoal, with magenta and lavender accents. At its best it‘s cool and beautiful, the perfect setting for a music which is traditional and sophisticated at the same time. At its worst it‘s like hanging out in the bar on Mars in Total Recall. The auditorium is packed, and folks are dressed up. Bluegrass is somewhat more conservative than Country, and the general look is blue suits and leather (not lizard) cowboy boots. The total Nashville Music Scene Look (blow dried and sequined) will be seen on the CMA show next week; meanwhile Owensboro is about as Nashville as Nashville is Hollywood, which is about 60%.

In the grand tradition established by the Oscars, the Ancient Greece of all Award Shows, the lesser awards are given first and then announced later between events. A posthumous Certificate of Merit goes to Lloyd Loar who created the Gibson F-5 mandolin (“giving the music its distinctive high lonesome sound”); another goes to “Uncle” Josh Graves who still plays dobro, Bluegrass’s slide steel guitar; and another to the Louvin Brothers, Charlie and Ira, who had never even heard of Bluegrass but sang it like angels anyway.

The Real Deal begins at eight, with an anonymous voice asking us for background fade-in applause and then counting down: “fifteen seconds to air, ten seconds, five, and Welcome, Everybody, to the Third Annual…etc.” The show is broadcast by satellite (from Outer Space no less) to thousands of radio stations including BBC and Armed Forces Radio, with the hope to be on TV next year hanging in the air like cigarette smoke.

The three Presenters of the Awards, Tim O‘Brien, Alison Krauss and Tom T. Hall, the Big Guns, are plenty big enough. Cue cards are flipped, envelopes are torn, and winners announced. Several of the big “crossover” nominees such as Emmy Lou Harris and Jerry Garcia are absent; though Harris, who “discovered” Ricky Skaggs (in the sense that Columbus “discovered” America) doesn’t have to demonstrate her credentials by showing up. The jokes are just bad enough, the sound system better than good enough. The little podiums are properly lucite and suspense is invoked like an absent god.

The three Presenters of the Awards, Tim O‘Brien, Alison Krauss and Tom T. Hall, the Big Guns, are plenty big enough. Cue cards are flipped, envelopes are torn, and winners announced. Several of the big “crossover” nominees such as Emmy Lou Harris and Jerry Garcia are absent; though Harris, who “discovered” Ricky Skaggs (in the sense that Columbus “discovered” America) doesn’t have to demonstrate her credentials by showing up. The jokes are just bad enough, the sound system better than good enough. The little podiums are properly lucite and suspense is invoked like an absent god.

Perhaps because with his wide bullfrog mouth he looks a little like Ralph Edwards, I expect Tom T. Hall to be a slick and smooth emcee. He is both, with the correct accent to boot. Tim O’Brien, who led the band Hot Rize to fame, aims to please. Alison Krauss hits the bulls-eye. She and O‘Brien won top awards the last two years. This year top honors go to the Nashville Bluegrass Band (Entertainer of the Year), Laurie Lewis (Female Vocalist), Del McCoury (Male Vocalist for the third straight time) and to dobro wizard Jerry Douglas, who seems to produce and play on every acoustic recording in Nashville. The between envelope acts are straight ahead and faultless but fairly predictable, at least until the Nashville Bluegrass Band brings out the Fairfield Four, an old-time Black gospel quartet, and backs them up on an a-capella rendition of “Roll, Jordan, Roll” that brings the house to its feet.

Perhaps because with his wide bullfrog mouth he looks a little like Ralph Edwards, I expect Tom T. Hall to be a slick and smooth emcee. He is both, with the correct accent to boot. Tim O’Brien, who led the band Hot Rize to fame, aims to please. Alison Krauss hits the bulls-eye. She and O‘Brien won top awards the last two years. This year top honors go to the Nashville Bluegrass Band (Entertainer of the Year), Laurie Lewis (Female Vocalist), Del McCoury (Male Vocalist for the third straight time) and to dobro wizard Jerry Douglas, who seems to produce and play on every acoustic recording in Nashville. The between envelope acts are straight ahead and faultless but fairly predictable, at least until the Nashville Bluegrass Band brings out the Fairfield Four, an old-time Black gospel quartet, and backs them up on an a-capella rendition of “Roll, Jordan, Roll” that brings the house to its feet.

Ralph Stanley accepts induction into the Hall of Honor for himself and his brother Carter, who died in 1966. The Reno Brothers accept for their father and his partner, Reno and Smiley, and these two legendary bands join Bill Monroe, Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs in the IBMA‘s Valhalla. Then in the high point of the evening, Tom T. Hall joins the Reno Brothers and Larry Sparks to sing the Stanley Brothers‘ haunting “Rank Strangers,” surely the saddest song ever written, calling Ralph Stanley on stage for the last verse and chorus: “I knew not their names and I knew not their faces,” as his high part pulls us back home, and as Mike Seeger says later, “Everyone floated up out of their seats and everyone remembers, if only for a moment, where it all began and what it‘s all about.” Country music, in all its forms, is all about loss.

Ralph Stanley accepts induction into the Hall of Honor for himself and his brother Carter, who died in 1966. The Reno Brothers accept for their father and his partner, Reno and Smiley, and these two legendary bands join Bill Monroe, Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs in the IBMA‘s Valhalla. Then in the high point of the evening, Tom T. Hall joins the Reno Brothers and Larry Sparks to sing the Stanley Brothers‘ haunting “Rank Strangers,” surely the saddest song ever written, calling Ralph Stanley on stage for the last verse and chorus: “I knew not their names and I knew not their faces,” as his high part pulls us back home, and as Mike Seeger says later, “Everyone floated up out of their seats and everyone remembers, if only for a moment, where it all began and what it‘s all about.” Country music, in all its forms, is all about loss.

AFTER YEARS OF PLAYING SUMMER FESTIVALS for a hundred bucks and a free campsite, Bluegrass‘s rank and file are glad to see the music becoming more businesslike. The Trade Show (closed to the public every day but Friday) is in the International Room, an area of the Executive Inn usually devoted to making high school reunions suitably dismal. Now it‘s bright and noisy, filled with booths displaying instructional tapes, instruments (Gibson is not here this year, but Martin is a big presence), instrument cases hard and soft, record companies old and new, strings, magazines (Bluegrass Unlimited is the Variety of the trade), plastic and sequined novelty items, pickups and electronics (precisely because the music is acoustic, Bluegrass players are very particular about their sound equipment), and several up-and-coming bands, handing out press packets and bios and photos and tape casettes. A few events such as Tulsa‘s Bluegrass and Chili Festival also promote themselves.

I wander around and talk to folks. Bill Keith lounges on a couch. John McEuen chats up a few old friends. Some of these people have known one another for years. I know none, but know of them all.

“How‘d I get into Bluegrass? I was into Elvis Costello when I met my wife. She was a fiddler, and she gave me a Martin D-18 so I could back her up at fiddle contests. When somebody gives you a D-18, you learn to play it”

“We‘re here to showcase, to meet people. Not musicians; you meet musicians on the road. Here you meet the people who get you bookings. Excuse me if I sound like it‘s a business. But hey, it‘s a business.”

Friday’s Showcase Luncheon Friday features the Cluster Pluckers and the Traditional Grass. Two more dissimilar bands could hardly be imagined—the one young moderns from Tennessee, the other a bunch of old guys in gray suits from Ohio. I‘m sitting with the Rarely Herd, who assure me that their name is an independently arrived-at pun and not a knock-off of the Seldom Scene, the famous DC area band. They showcased here yesterday.

Showcase bands must audition and are selected by a special committee of the IBMA. What‘s it like, playing for a room full of professionals? “Hard. If you make a mistake you don‘t blink, you just move right along.” But isn‘t that the way it‘s done anyway? I wonder. The show is going out over the a syndicated Bluegrass network sponsored by Martin Guitars and Jim Walter Homes, a popular builder in the South somewhere between a mobile home and a real house.

On the river a string of barges piled with coal slides slowly by. All this is new to me–the Owensboro I left behind for New York turned its back to the river. The view is impressive. The gray-suited guys from Ohio play straight-ahead bluegrass and the crowd loves it. “Plowing all the way to the fence,” it‘s called. They close with an old gospel number about a man impatient to die so he can join his wife, and they get (or the old man and his dead wife get) a standing ovation.

“I‘d hate to have to follow them,” one of the Rarely Herd observes. The food arrives. Grits and eggs. (The cheapskates are serving us breakfast!) The Cluster Pluckers, a hot little band with a name like a bad haircut, leap onstage and start off with a folksy Gordon Lightfoot-type song, which the crowd doesn‘t buy. Plus there are two girls in the band and the guitar player is wearing a day-glo hat. Then they play an old Carter Family tune and all is forgiven. In Bluegrass repertoire is everything, and every band (and certainly these savvy newcomers) has the key to the old cabin on the hill.

In 1960 I left Owensboro for college in the fabled North, packing my Thelonious Monk and Miles Davis LPs. I was surprised, even a little dismayed, to find the sophisticated intellectuals I had always dreamed of meeting wearing denim work shirts and playing Flatt and Scruggs. “From Kentucky?” they said. “Far out! Who do you like best, Bill Monroe or Flatt and Scruggs.” “I like them all about the same,” I said, which was true. I had avoided them all. But I was a fast learner, and the next time my mother (who had left Calhoun, Kentucky, for the biggest town around) called from Owensboro; she heard bluegrass in the background and asked: “Where are you calling from, anyway?”

THE FAN FEST STARTS FRIDAY. The site is the old dam where as teenagers we hung out to drink and ride the “bear traps” across the spillway. Now the dam is gone and the river flows smoothly past concrete ruins overgrown with kudzu. The parking lot at the top of the riverbank is filled with RVs from Ontario, Indiana, Missouri, Georgia, Illinois, Tennessee and Texas. Clusters of fans (many of whom are players) are gathered here and there in impromptu bands with too many guitars. The little Japanese lamps that snowbirds seem to love are strung in rows along the awnings of the trailers.

The old dam area, now called English Park, is roped off for the Fan Fest ($39 for three days) and inside, vendors are selling funnel cakes (a sort of zeppole cleverly designed to look like intestines), barbecue featuring Owensboro‘s famous hickory-smoked mutton; catfish fiddlers and hush puppies of course; Moon pies and Polish sausages. No beer. Drinking at Bluegrass festivals is often tolerated but never encouraged; even though Bluegrass has gone urban and modern, such a betrayal of its Bible Belt heritage would set so many old-timers to rolling over in so many graves that it would break the Richter scale.

A concrete floodwall extending down the high bank of the river makes perfect bleachers, and at the bottom on the flat between the wall and the water, fans and festival goers are already setting out lawn chairs in the music festival ritual that allows them to claim and hold a spot for the duration. The stage is a blue geodesic tent structure that looks like the shark from Jaws rising from the Ohio, teeth (lights) and all. The sound is perfect, so bright and loud that I wonder how Bluegrass can still be called acoustic. Signs selling cellular phones, chewing tobacco, guitars and mobile homes offer a quick cultural cross-section of the crowd.

A concrete floodwall extending down the high bank of the river makes perfect bleachers, and at the bottom on the flat between the wall and the water, fans and festival goers are already setting out lawn chairs in the music festival ritual that allows them to claim and hold a spot for the duration. The stage is a blue geodesic tent structure that looks like the shark from Jaws rising from the Ohio, teeth (lights) and all. The sound is perfect, so bright and loud that I wonder how Bluegrass can still be called acoustic. Signs selling cellular phones, chewing tobacco, guitars and mobile homes offer a quick cultural cross-section of the crowd.

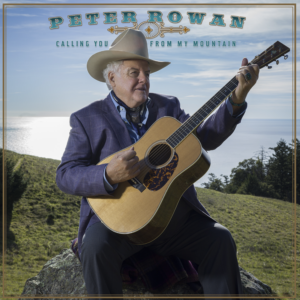

The Fan Fest opens with Peter Rowan, one of the New England folkies who was drawn to the music in the early 60s and was good enough to be nabbed by Bill Monroe. The Nashville Bluegrass Band follows, heavy into the gospel harmonies that the fans love. Don‘t be thinking bluegrass is all about speed and instrumental hot licks; it‘s at least half high sweet shape-note gospel harmonies that that will take you to Heaven even if you don‘t believe in it anymore. A perfect sound for a late September day with just a brush of fall in the sycamores on the Indiana shore.  At one side of the stage little boys and their dads line up to buy slushies and barbecue. A lonely clogger performs on a plywood 4X8. A couple of gray-haired college professors surreptitiously smoke a joint in the weeds on the river bank. A ski-doo drifts by, picking up free sounds, while a coal barge slips under the same two-lane bridge that Bill Monroe drove over on his way to Chicago to make history by shifting old-time Country music into overdrive, fifty years ago.

At one side of the stage little boys and their dads line up to buy slushies and barbecue. A lonely clogger performs on a plywood 4X8. A couple of gray-haired college professors surreptitiously smoke a joint in the weeds on the river bank. A ski-doo drifts by, picking up free sounds, while a coal barge slips under the same two-lane bridge that Bill Monroe drove over on his way to Chicago to make history by shifting old-time Country music into overdrive, fifty years ago.

Even though Bill Monroe is from the Owensboro area, calling this northward-looking city the home of Bluegrass is a bit of a stretch. If the music has a home-place, it‘s the five-state mountain area of upper east Tennessee, southwest Virginia, eastern Kentucky, southern West Virginia and western North Carolina. This is the heartland of the Appalachian South, and it‘s where the roots of the music lay. Yet the hill country culture long ago spread like kudzu far beyond the mountains. Its accents and folkways are found all the way west into Oklahoma and Texas, north into southern Indiana and Ohio, and south into the red clay hills of Mississippi and Louisiana. The mountains cast a long shadow across the South. Even if it‘s not the heartland, western Kentucky can claim not only Bill Monroe and Merle

Travis, but a later “brother” act whose Louvin-influenced harmonies helped shape rock and roll via the Beatles and the Beach Boys—the Everly Brothers.

The Fan Fest rolls on all day and deep into the night as the barges slide past on the river. Alison Kraus wrings out her band and then brings on the Cox Family, an old-fashioned gospel act from northern Louisiana. Mike Seeger, wandering around the concession area, thinks they are just about the best thing at the festival besides the barbecue, and I agree. As it gets dark, Doyle Lawson brings on his band, Quicksilver. One of Bluegrass‘s preeminent mandolin players, Lawson is second or third generation, depending on how you count.

ALMOST EVERY IMPORTANT MUSICIAN in the first generation, both Flatt and Scruggs, Jimmy Martin and Don Reno, spent time in Bill Monroe‘s band. Most of the important musicians in the later generations, Doyle Lawson, Ricky Skaggs, J.D. Crowe, Sam Bush, Keith Whitley and Larry Sparks passed through their bands or the Stanley Brothers Band or the Country Gentlemen. That tradition continues today as Lawson competes with his own progeny, IIIrd Time Out, for festival space. This active and demanding apprenticeship system keeps the music tied by blood and sound to the rural South. Anyone who wonders if the system works has only has to sit and listen; Quicksilver plays with precison and passion, the authentic old-time stuff. Forty years ago when Bluegrass was new, Jimmy Martin was asked what was so special about it. “What‘s special about it,” he said, “is that it‘s perfect.” Still is.

ALMOST EVERY IMPORTANT MUSICIAN in the first generation, both Flatt and Scruggs, Jimmy Martin and Don Reno, spent time in Bill Monroe‘s band. Most of the important musicians in the later generations, Doyle Lawson, Ricky Skaggs, J.D. Crowe, Sam Bush, Keith Whitley and Larry Sparks passed through their bands or the Stanley Brothers Band or the Country Gentlemen. That tradition continues today as Lawson competes with his own progeny, IIIrd Time Out, for festival space. This active and demanding apprenticeship system keeps the music tied by blood and sound to the rural South. Anyone who wonders if the system works has only has to sit and listen; Quicksilver plays with precison and passion, the authentic old-time stuff. Forty years ago when Bluegrass was new, Jimmy Martin was asked what was so special about it. “What‘s special about it,” he said, “is that it‘s perfect.” Still is.

The exhibitors for the Fan Fest are set up in an old building that once was used for dam maintenance. It‘s an open-air structure that looks like a log corncrib redecorated by Escher. Downstairs there are videos of the Country Gentlemen reunion (at Woodstock, no less) for sale–plus sequined patches, magazine subscriptions, and instruments old and new: Martin and Santa Cruz guitars, mandolins like jewel boxes, inlaid rhinestone-encrusted banjos worthy of the band of Krishna. I help my cousin, the proprietor of Gordon‘s String Music in Tallahassee, Florida, set up. Gordon plays in three bands—one Celtic, one Old-Time (Bluegrass without the solos) and one Bluegrass. A skilled luthier, he sells, trades, and fixes mandolins, guitars and a few fiddles. Watching him and the people who come by, I realize that Bluegrass people love the instruments for how they look as well as how they sound.

“I never saw an instrument that sounded right that wasn’t made right,” says Gordon as he examines the finish on a Flatiron, one of the few modern mandolins that can match the “bark” of the classic Gibson F-5. “After a certain point the detail on an instrument has nothing to do with the sound; and yet it can tell you everything.”

Martin guitars are like antiques: the older the better. They run from fifteen hundred up to a hundred grand. “The guy who owned this D18 smoked so much that it got this beautiful dark color, like a country ham. When he died his widow sold it to me. What did he die of? What do you think he died of?”

Martins are priced by serial number, model and condition. Fiddles are priced more arbitrarily. Here‘s one for $350. The one next to it is $850. They sound about the same. The bows cost $500. ”$500 for a bow?” “That‘s nothing,” says a woman who is trying out the fiddles. ”Isaac Stern once paid $100,000 for a bow.”

“Hell,” says a good old boy listening in, “if I had a hundred grand, I‘d just hire a fiddle player to follow me around and play. That’d leave me both hands free.”

People stroll in and out of the pavilion, taking a break from the music, perhaps to make their own. Anyone who picks up an instrument on display is (usually) good enough to show off a little. Bluegrass is all about showing off. If it‘s a mandolin or fiddle player, the exhibitors will play a little guitar to back them up. “Sounds good. What kind of mandolin do you play? Not bad; they can be pretty decent. You’re about ready to move up though. We could probably make a trade.”

My cousin Gordon was with J.D. Crowe‘s Kentucky Mountain Boys, back in the 60s when they were the featured act at Miss Martin’s in Lexington; back when Ricky Skaggs was still a kid picking up hot licks and Keith Whitley hadn‘t yet crossed over to Country and started his long, slow alcohol suicide.

My cousin Gordon was with J.D. Crowe‘s Kentucky Mountain Boys, back in the 60s when they were the featured act at Miss Martin’s in Lexington; back when Ricky Skaggs was still a kid picking up hot licks and Keith Whitley hadn‘t yet crossed over to Country and started his long, slow alcohol suicide.

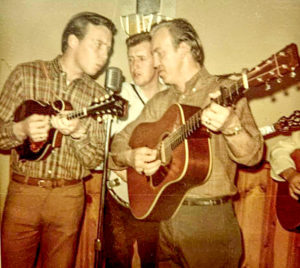

“I played mandolin and Doyle played lead guitar,” Gordon reminisces. “I didn‘t even know he played mandolin. One day we were working out a song and Doyle asked me to switch so he could show me a mandolin break. Hell, I wouldn‘t even touch a mandolin after that for ten years.” Bluegrass is all about showing off. Even among friends. Especially among friends.

FRIDAY NIGHT THERE ARE PARTIES, WILD AND LATE, at the Big E and all over town. Down by the dam late at night, the mysterious ”Men of Wealth and Taste” pick out alternate gospel tunes, the dark ones that will never be recorded or played on stage—

“God Sent an Angel Down to Kill Her”

“Tearing the Pages from the Old Family Bible”

“Have You Heard They‘ve Sold the Throne?”

“Will I Have to See His Face?”

“What a Shame there is no God”

—then disappear before the dawn.

Saturday Morning begins with the Owensboro premiere of a new 90- minute documentary called High Lonesome. It‘s too long by half, repetitive, folds western Kentucky into the Appalachians, dwells on the Father of Bluegrass (Monroe) but leaves out most of the aunts, uncles, brothers, sisters, and black sheep; omits the explosive influence of the Northeast via the folk revival; skimps on the Stanley Brothers and Reno and Smiley, not to mention the Louvins and the vocal harmonies; and in fact never deals with the instrumentation, the sound or the technical aspects of the music. Other than that, it‘s fine.

Saturday is rainy rainy rainy but the fans show up anyway, in their green and yellow lawn chairs and yellow slickers looking, as a local reporter puts it, like a quilt left out in the rain. The Russian group Kukuruza are smart enough not to try any complicated vocal harmonies but let their talented female vocalist carries the load. They are followed through the day by several standard Bluegrass bands. One of the weaknesses of Bluegrass is that after a while it begins to all sound alike. Precision without passion. A lot of the younger musicians in particular are Nashville session players, talented but generic.

Then along comes Charlie Waller and the Country Gentlemen, reminding us that the bands that last are the bands that add to or change Bluegrass. Bill Monroe and his Bluegrass Boys “made” the mandolin. Flatt and Scruggs “made” the banjo and the dobro. The Stanley Brothers established the guitar as a lead instrument. Waller‘s contributions have been vocal. In its earlier incarnations in the DC area, his band helped popularize Bluegrass with the younger urban generation, by emphasizing rather than diluting the music‘s Southern gospel roots. Charlie Waller is the Phil Spector of Bluegrass, building a seamless wall of sound. Even in the rain.

BACK AT THE EXHIBITORS‘ PAVILION, my cousin Gordon is looking over a mandolin. The owner, who looks like a Hell‘s Angel out of uniform, bought it from a dealer in Illinois a few months ago, and now has his doubts; he wants to know if it‘s genuine.

Gordon holds the “Gibson” gingerly like a wet baby; turns it over, looks inside it with a little mirror like a mother peering down the back of a diaper. He passes it to Doyle Lawson, who has stopped by to visit; Doyle feels the florentine curls with his finger and shakes his head. Another mandolin player (who also builds wooden wind tunnel models for NASA) joins them, and looks at the glue and the finish on the neck.

Gordon holds the “Gibson” gingerly like a wet baby; turns it over, looks inside it with a little mirror like a mother peering down the back of a diaper. He passes it to Doyle Lawson, who has stopped by to visit; Doyle feels the florentine curls with his finger and shakes his head. Another mandolin player (who also builds wooden wind tunnel models for NASA) joins them, and looks at the glue and the finish on the neck.

“Gibson overproduced the F-5 in the 70s, but …”

“It‘s a little tight on the curl here.”

“I‘ve never known them to laminate neck stock.”

“See this inlay? Now understand, I don‘t mean to knock your mandolin, but …”

The consensus is that it‘s a Japanese copy (almost all Bluegrass mandolins copy the Gibson F-5 first played by Bill Monroe) and someone stripped the name off the head and laid in ”Gibson.” They even went to far as to include a Gibson ”owners‘ manual” in the case. This evidence of fraud offends us all. The owner walks off shaking his head and clenching his fists.

“Hope we didn‘t hurt his feelings,” Doyle says.

“He wanted to know,” the NASA model-maker says.

“I’d hate to be that dealer in Illinois when that old boy finds him,” Gordon ventures.

Back down on the riverfront, IIIrd Time Out, mostly Quicksilver alumni, are nattily dressed in the latest Gap colors. The sound is explosive; plus they are all young and handsome, with the blow-dried achey-breaky look. There are oohs and aahhs. In addition to their good looks they exhibit the first social consciousness I‘ve seen at the Fan Fest (outside of a few pathetic Ross Perot t-shirts) as they sing “Working More Now but Living Lower on the Hog.”

More social consciousness, as The Coon Creek Girls are joined by one of the old original Coon Creek Girls, reminding us that in the old days Bluegrass included some women and promising that the future will include more.

Back at the pavilion, out of the rain, two guys are fooling around with the Santa Cruz guitars. Both are mandolin players with different bands, and though they look like brothers and play seamless duets, they have never met. A crowd gathers as they run through a few standards and then a beautifully-improvised two-guitar “Norwegian Wood.”

BY SUNDAY MORNING THE RAIN IS GONE. The sky is clear and the fans who have drifted away are drifting back. The Ohio River looks blue and beautiful as it winds its way down toward the Mississippi. Barges filled with coal ripped from John Prine‘s Muhlenberg County slide by. A Colorado band open the day, followed by a Georgia band from the Vidalia onion country. Gordon sells two mandolins and could sell two more as he‘s closing up, but “Hell, I forgot my little credit card machine.” His Florida band opened for Jim and Jesse and the Virginia Boys a few months ago, and he drags me down the hill to catch their act before he heads back South and I head back to New York. It‘s fitting that one of the great old-time brother teams, with over forty years on the road, close the show which the forward-looking Peter Rowan opened. 7500 people have turned out, even in the rain, to hear forty bands, a virtual who‘s who of Bluegrass.

BY SUNDAY MORNING THE RAIN IS GONE. The sky is clear and the fans who have drifted away are drifting back. The Ohio River looks blue and beautiful as it winds its way down toward the Mississippi. Barges filled with coal ripped from John Prine‘s Muhlenberg County slide by. A Colorado band open the day, followed by a Georgia band from the Vidalia onion country. Gordon sells two mandolins and could sell two more as he‘s closing up, but “Hell, I forgot my little credit card machine.” His Florida band opened for Jim and Jesse and the Virginia Boys a few months ago, and he drags me down the hill to catch their act before he heads back South and I head back to New York. It‘s fitting that one of the great old-time brother teams, with over forty years on the road, close the show which the forward-looking Peter Rowan opened. 7500 people have turned out, even in the rain, to hear forty bands, a virtual who‘s who of Bluegrass.

My mother, God rest her soul, loved music, and so naturally she loved the 60s. When I brought my northern folkie friends home from college, she would sit up with us all night, drinking iced tea with Illinois vodka and listening to us play at playing. She loved it all, from Joan Baez to Bob Dylan to The Beach Boys, but she drew the line at Bill Monroe, born and raised in Rosine, forty miles from her childhood home in Calhoun, who could have been her older brother.

“It was tacky then and it‘s tacky now,” she used to say. She would still say the same today. But that‘s okay. Bluegrass, then and now, is all about leaving home and coming home, and in Owensboro it has found a home at last.

But alas, it was not to be. A few years later, the IBMA moved to Nashville, Country‘s Hollywood, where it truly belongs. The World of Bluegrass (and Awards Show) now plays In Raleigh, the biggest college town in the South.

But alas, it was not to be. A few years later, the IBMA moved to Nashville, Country‘s Hollywood, where it truly belongs. The World of Bluegrass (and Awards Show) now plays In Raleigh, the biggest college town in the South.

Did I mention that that Bluegrass, the fans and the players and the business as well, was all white folks? It was understood. Rhiannon Giddens and the Carolina Chocolate Drops, changed all that for the better, somewhat. A deeper understanding.

The Bluegrass Hall of Honors(Fame) is still in Owensboro, and big acts still play along the river. Giddens draws huge crowds.

The Bluegrass Hall of Honors(Fame) is still in Owensboro, and big acts still play along the river. Giddens draws huge crowds.

But this story was obsolete even as it was written (around 1993) and never published anywhere; but here.